أفكار حُـرّة : رئيس التحرير محمد حسين النجفي

صوت معتدل للدفاع عن حقوق الأنسان والعدالة الأجتماعية مع اهتمام خاص بشؤون العراق

Memorable experience at Iraqi ER

During the summer of 1966, my appendix became so painful that it required immediate medical attention. I told my father that I would like to have the operation done at the Central Public Hospital. He refused to allow me to attend a public hospital because we were a middle class family and we could afford to be treated at a private hospital. But I was a populist; I explained to my father that I am not the type of kid that wanted to be treated like an elitist. I wanted to experience medical treatment like ordinary people, whether it was great or miserable, simple or complicated, successful or failure.

|

While my father understood my position, he was concerned that people would think we were just trying to save money. I didn’t care what people thought or said though. My father and I were unable to reach an agreement, so we got my uncles involved. Uncle Mohsen proposed a compromise. His friend was a military officer who had a friend who was a surgeon at the public ER hospital located in downtown Baghdad. That way, I’d get the public hospital while my father would get some peace of mind. Finally, we had an agreement.

My father, my Uncle Mohsen, his friend the officer and I went to the ER to meet the surgeon and everything was ready for the operation. Before the start of the anesthesia, the surgeon asked a nurse to turn on the radio and search for the new songs of one of the most famous Arabic singers, then and now, “Umm Kulthum”. At that time, the songs “You are my age” and “You are the Love” were being played day and night on most of the Arabic Radio stations. And finally they agreed that the operation will be performed while listening to the tune of “You are my age”.

While I was stretched out on the operating table, the surgeon was excited and waiving the cutting blade in his hand with the music. I became worried, but I told myself perhaps it is the self-confidence of young doctors. Maybe this is modern medicine. Yes, they are young doctors and from a modern medicine school! Or are they indifferent, careless and the lives of their patients aren’t of great concern? After seeing that, I started to appreciate my family’s insistence for private care. And while we were in the middle of the great musical introduction of one of the most famous Arabic music composers Mohamed Abdel-Wahab, and before Umm Kulthum’s throbbing voice cracked her influential singing, the effects of the anesthetic started working. As the sergeant said, I woke up just before the song finished.

In the recovery room, there were two beds – in the first bed was an old man and the second was for me. His bed was closer to the door, while my bed was closer to the window. Since we were in the middle of the first class Iraqi summer heat, sleeping near the window was a treat.

I woke up on the second day and the nurse asked me to walk the corridors of the hospital to stimulate throwing up, to empty my stomach from the residue of the anesthesia. As I did so, I tried to identify some faces, what was happening in the corridors of the hospital to the people, the events and their stories. While I was walking around I felt nauseated and went to the bathroom and vomited; a bitter ugly flavor shook all of my body. But afterwards I felt very comfortable as if a dragon had been buried in my chest and I had got rid of it.

I went to my room and there waiting for me was the assigned housekeeper. He was very slim and very tall. From his general look I could tell that he was from the southern part of Iraq and most likely he was a resident of the city of Al-Thourah (Revolution) which is one of the poorest districts in Baghdad. He asked me about my name and told me that his name is Shabboot (“Carp”). This was the first time I heard of a person named Carp, which is a kind of fine Iraqi river fish. Shabboot was a very funny, jolly guy, and had all the gossip about the doctors, nurses, patients and whatever went on between them. He began to tell me about the gangster who was stabbed by a knife in the Kurd District in downtown Baghdad; the case of the prostitute, who was attacked by five of the hustlers repeatedly through the night, and would have bled to death if the ER didn’t save her life; the boy who was molested and raped by his PE teacher and many other amazing stories that are unheard of in private hospitals and bourgeois societies.

I asked him about a girl I saw strolling down the aisle wearing a semi-transparent silky black dish-dasha (nightgown). She had a beautiful tanned face, with long black hair and a slim figure, but the expression on her face was very sad and lost and looked like there was no life in it. I asked Shabboot what was her story? Shabboot could not begin to speak before lighting his cigarette. Her story was that she was betrayed and abandoned by her lover who ended up marrying another girl. She set herself on fire, burning her whole body, except for her face. She wanted to die but medicine did not have mercy on her and kept her alive to suffer. She had lost her beloved and lost her body, and the soul remained confused between sorrow and remorse. I saw the impact in the glare of Shabboot’s eyes and in the grave tone of his words. Yes, everyone sympathized and empathized with her, but what were her feelings and what was she thinking?

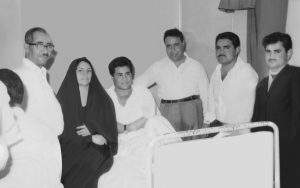

That same afternoon I got the grand visit by my father, my mother, my uncles Mahdi, Mohsen, and Karim. They came loaded with all kinds of food, fruits, and meat. They were like going to a picnic. We started to eat all of them and my uncle Mahdi insisted to cut a big watermelon in order to cool our hearts from the heat of the summer. My mother said to spare the boiled chicken for my dinner and that I have to eat it, because I needed to make up for the loss of blood and my face looked very pale. She did not let anyone touch that chicken. It was a family gathering of the nicest kind, regularly interrupted by jokes and laughter from all, particularly uncle Mahdi. My father was tired of the disease that began to appear on his face. But on that day I was the patient and I was the center of attention, where I was then the first child in the family and the center of attention of all its members.

Everyone left, and after that delicious food I fell in a deep summer afternoon nap. I woke up hearing Shabboot screaming, cursing the cat that stole my chicken dinner and ate it. Then he asked me, ‘Why did you leave the window open? “Abu-Jassim,” (Nick name for Mohammad), don’t you know that the cats here are waiting for such golden opportunities?’ He continued with his exaggerated act to prove that the cat stole the chicken and not him. I examined the pan, it was not flipped and there was no spill on the floor. It was obvious piracy to eat my chicken. I asked Shabboot in a sarcastic way if the cat had left any piece of meat for me. He shied away and told me that tonight the hospital food was great and my dinner was on him. I couldn’t be hard on Shabboot because I liked him. He was a very simple man tempted to eat delicious chicken without affecting the health of an obviously rich boy in a public ER. I kept asking him how did the cat grab the chicken and run. Each time he gave different details and we both laughed and laughed and laughed.

Mohammad H Alnajafi

mhalnajafi.org

April 26,2018

I remember when you read this story to us when you first visited our family. I love your stories so much Amu!

Love,

Kyan

One of your best stories amu. Very interesting and a bit funny 10/10

Thank you Hasan for 10/10 score. Are you sure this score not influenced by the blood relationship? I put extra effort to write in English. So I can reach our new young generation and to tell them some of our history, culture and ethics. For each story there is hidden and obvious morale between the lines. I am sure you got both. Thank you for taking the time to read it. love my challenging nephew.